The Library

7 March - 14 April

Soup presents the gallery’s sixth exhibition, Nina Silverberg’s debut solo exhibition ‘The Library’. Silverberg (b. 1994) is an Italian painter living and working in London. She received her BA in Fine Art from City and Guilds of London Art School in 2018.

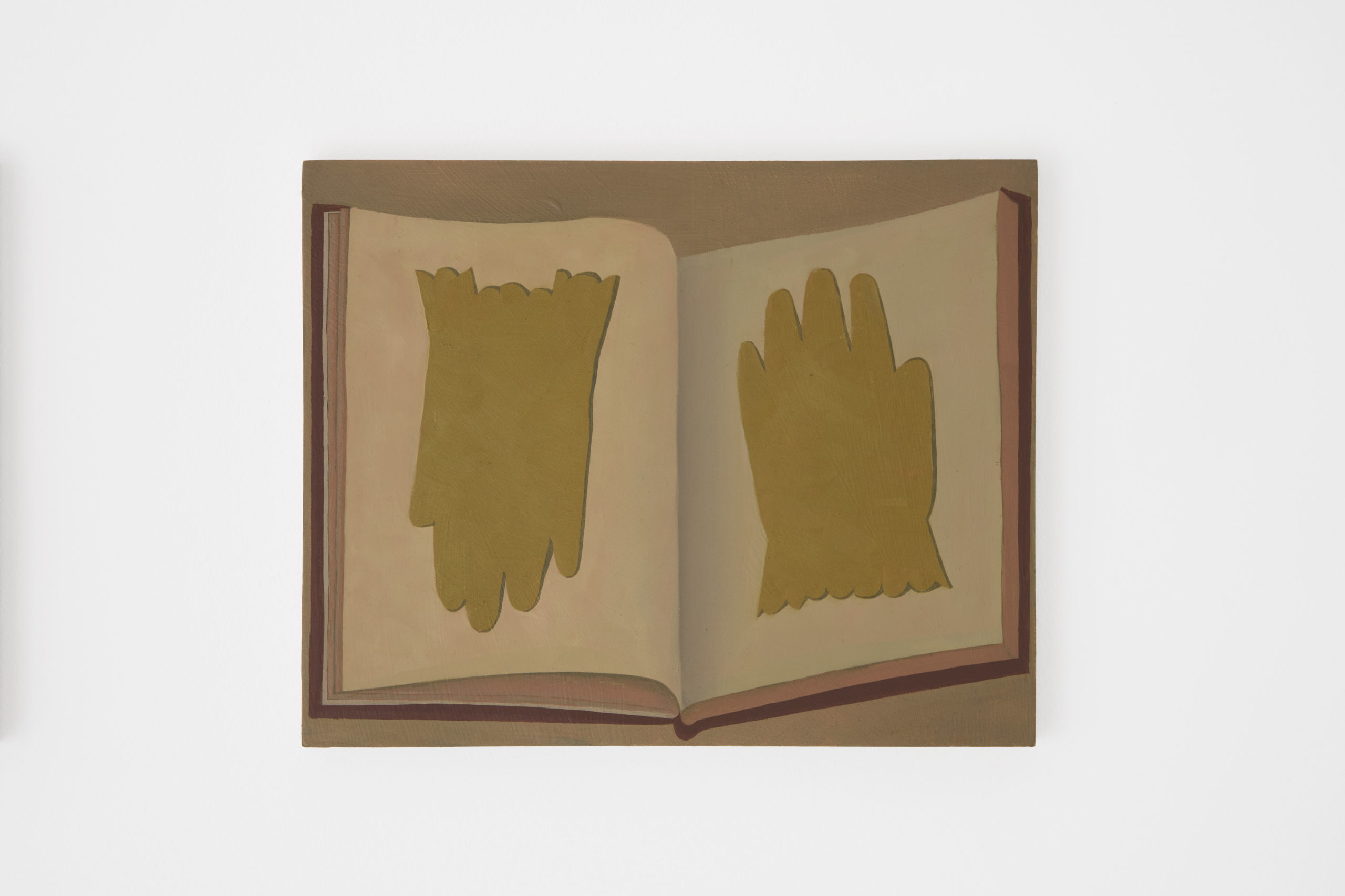

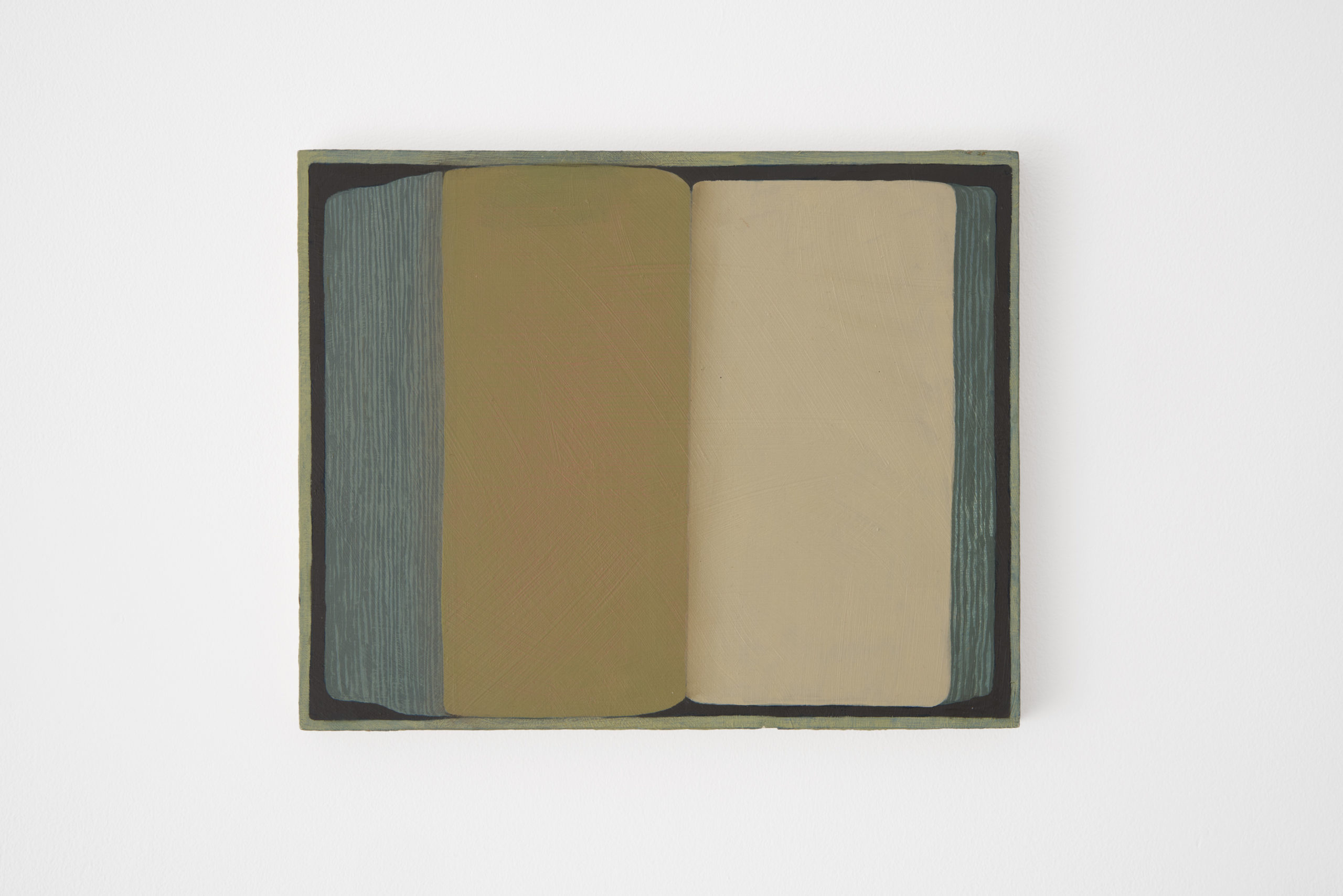

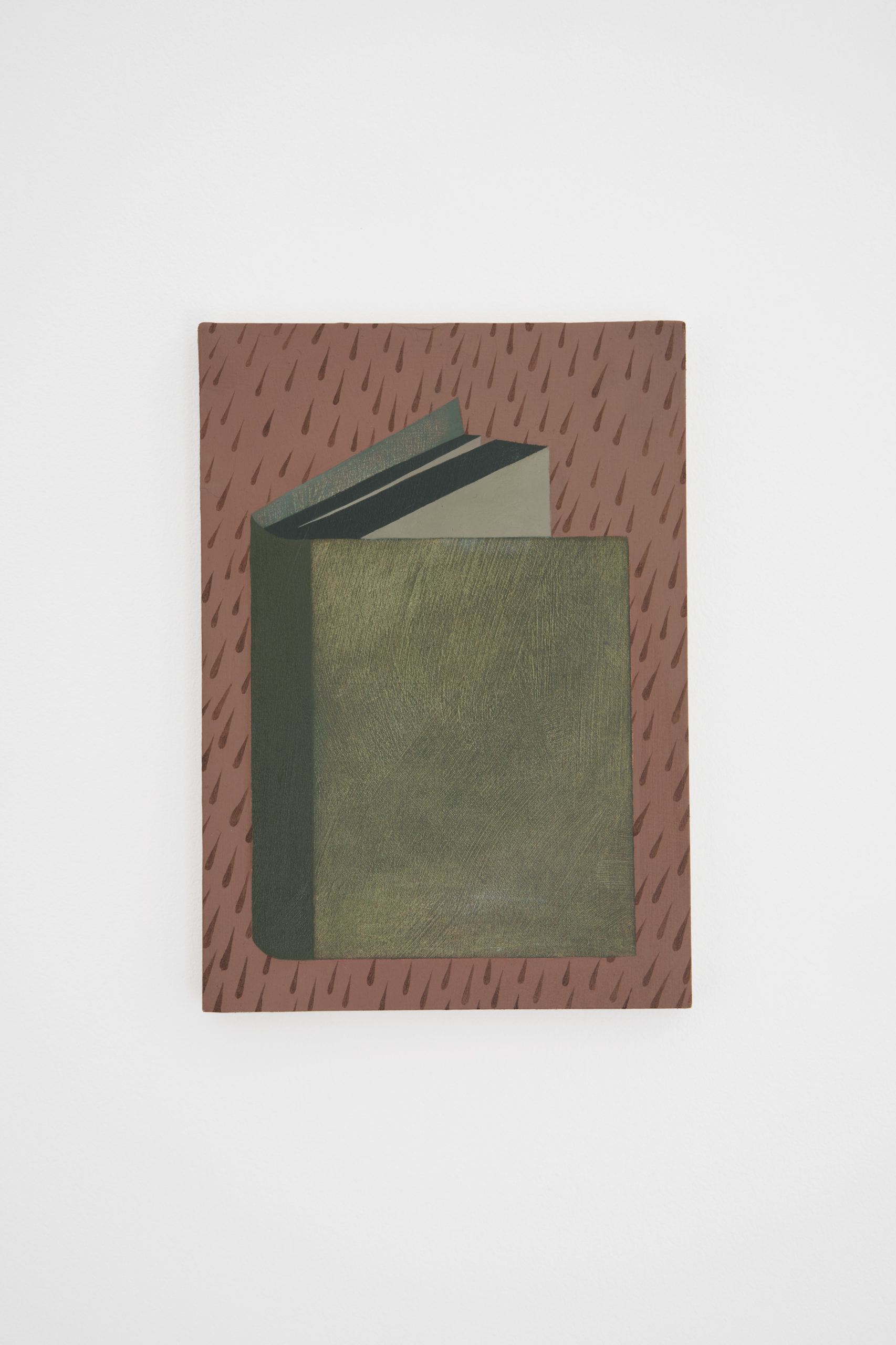

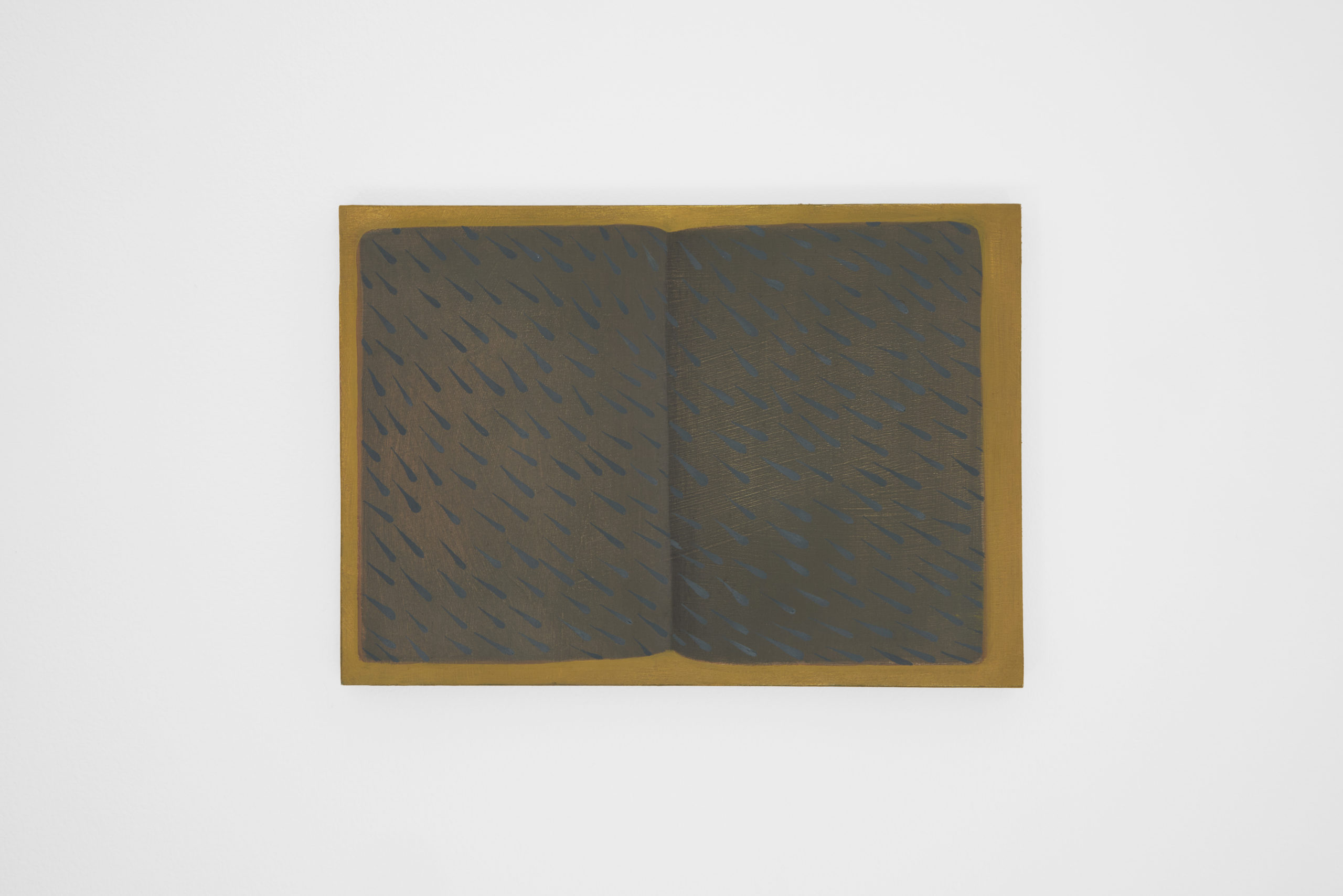

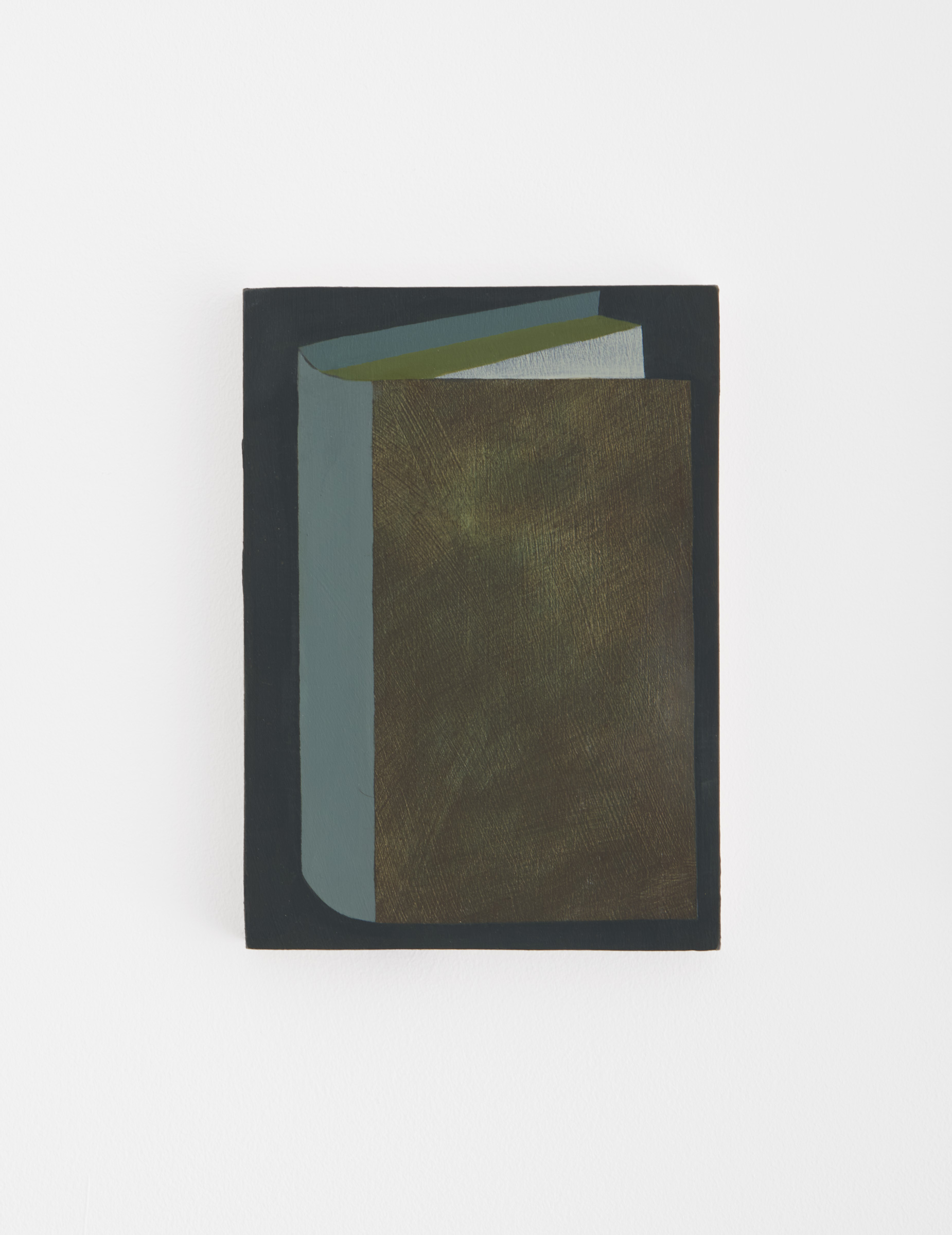

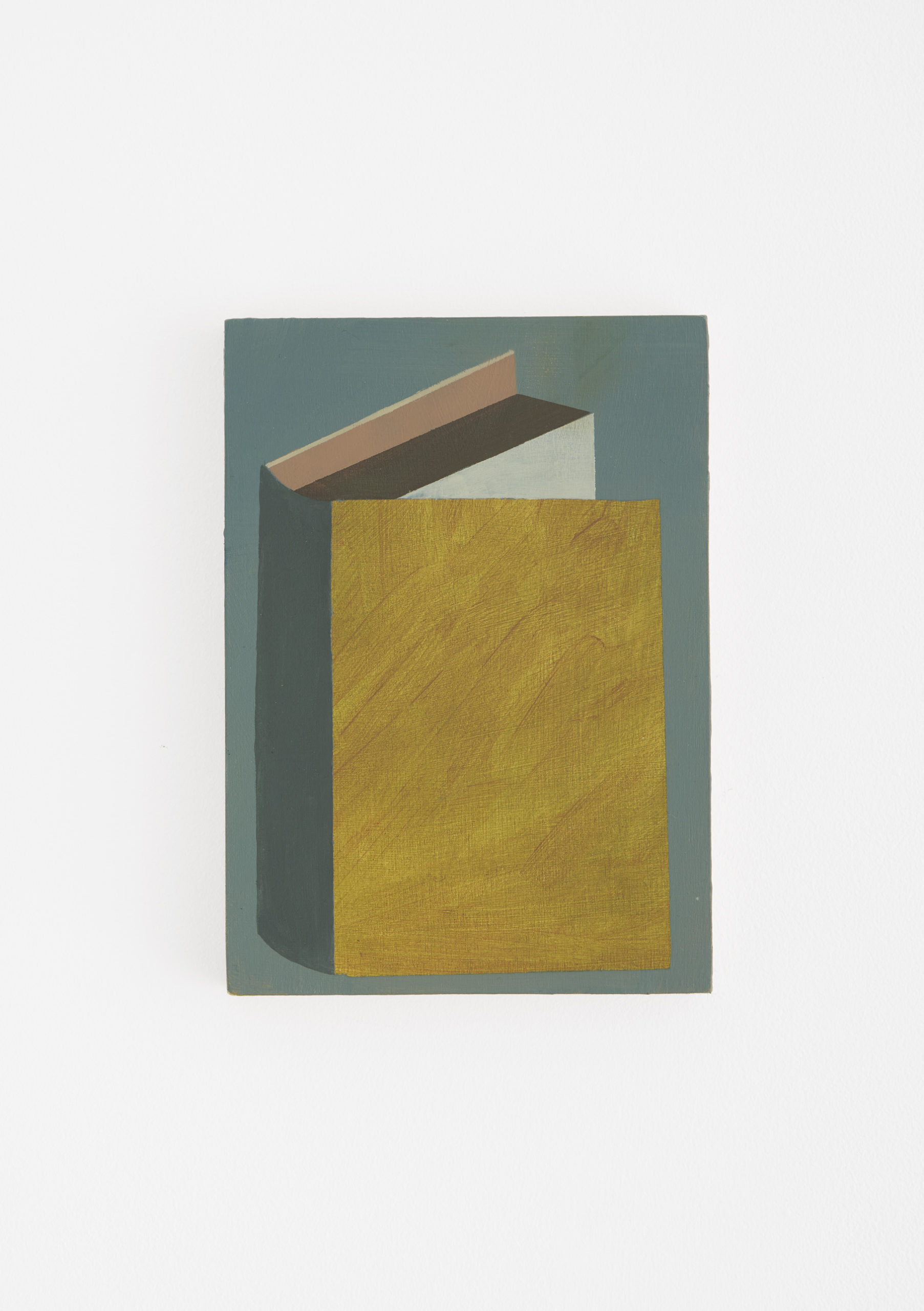

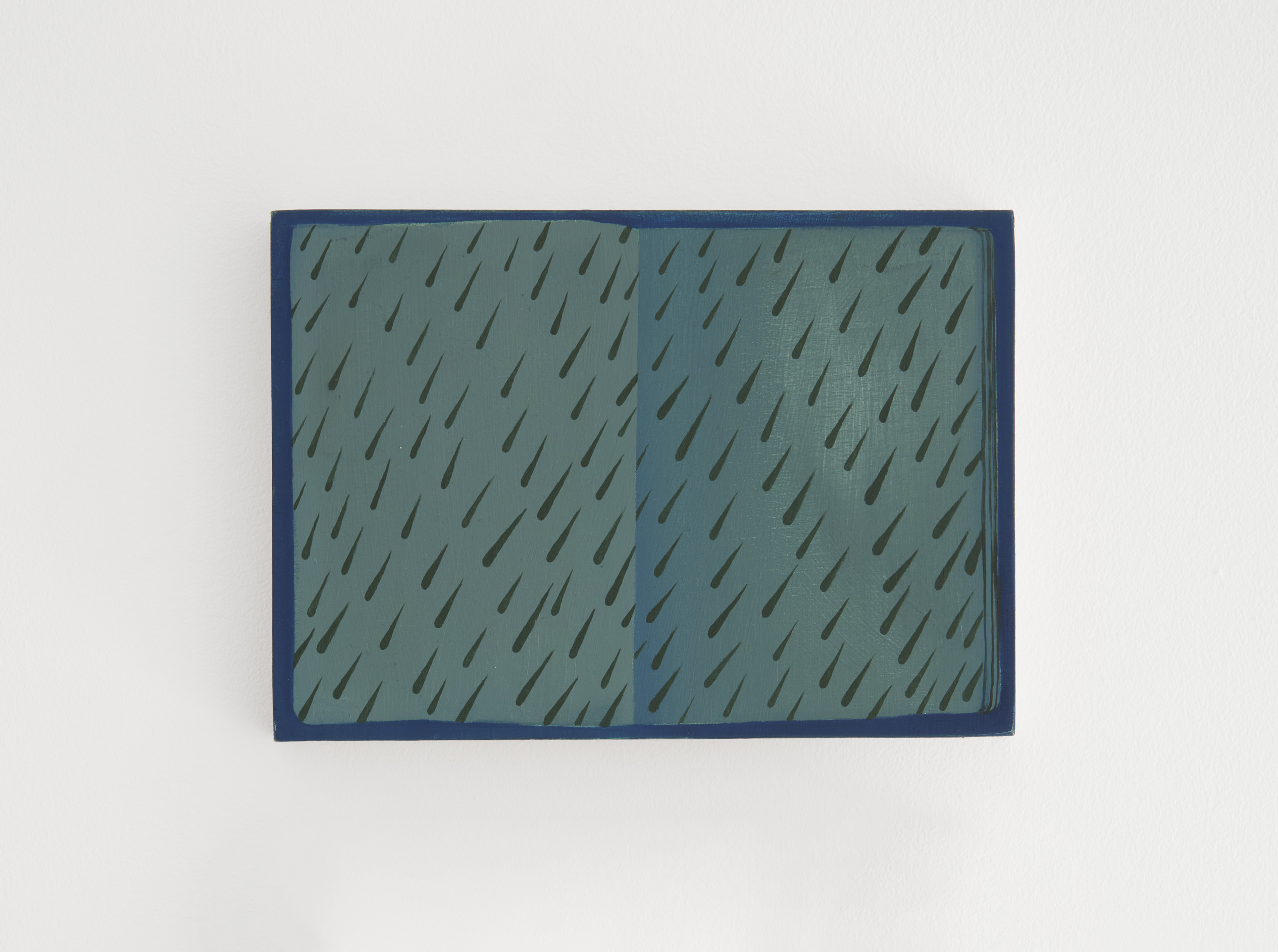

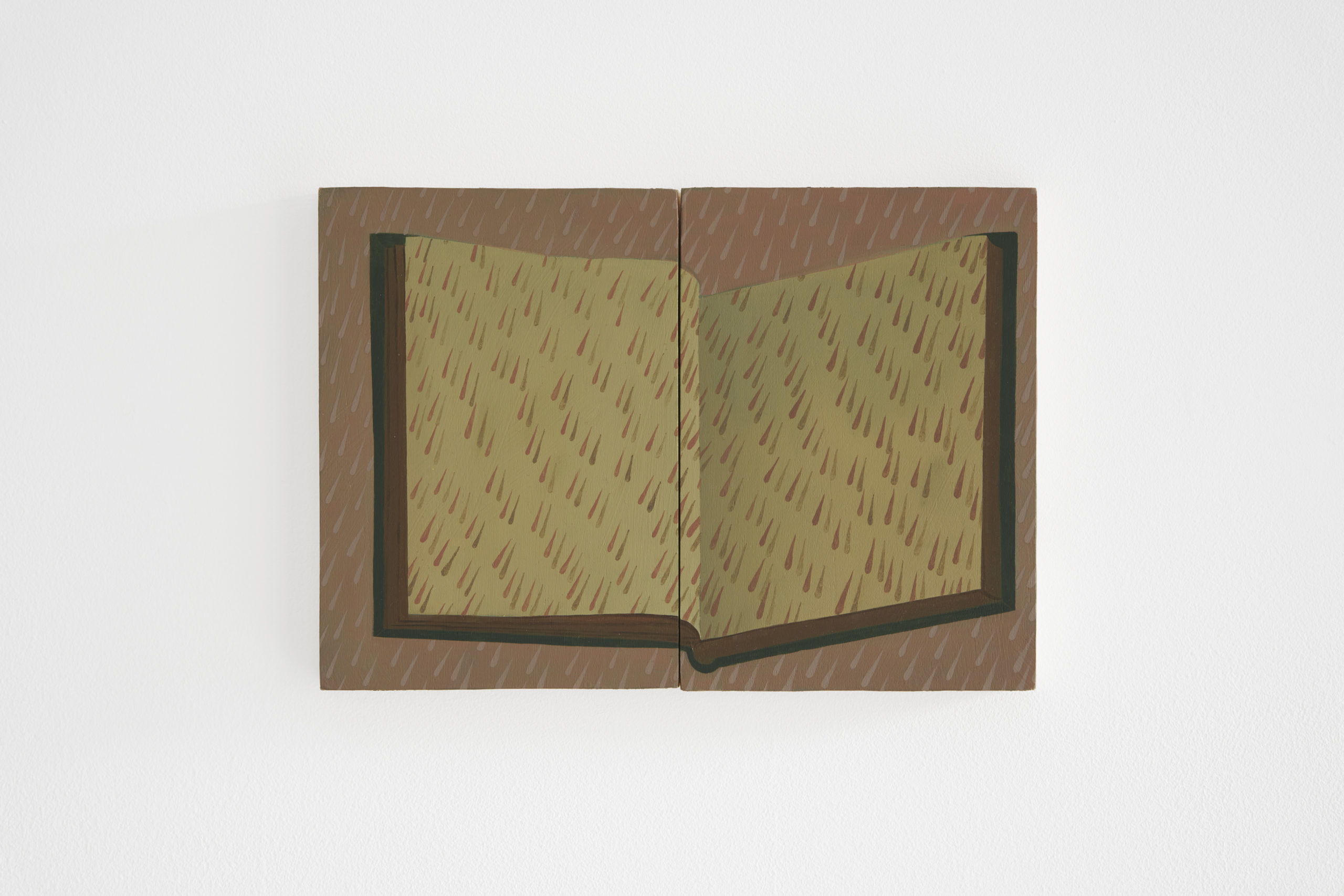

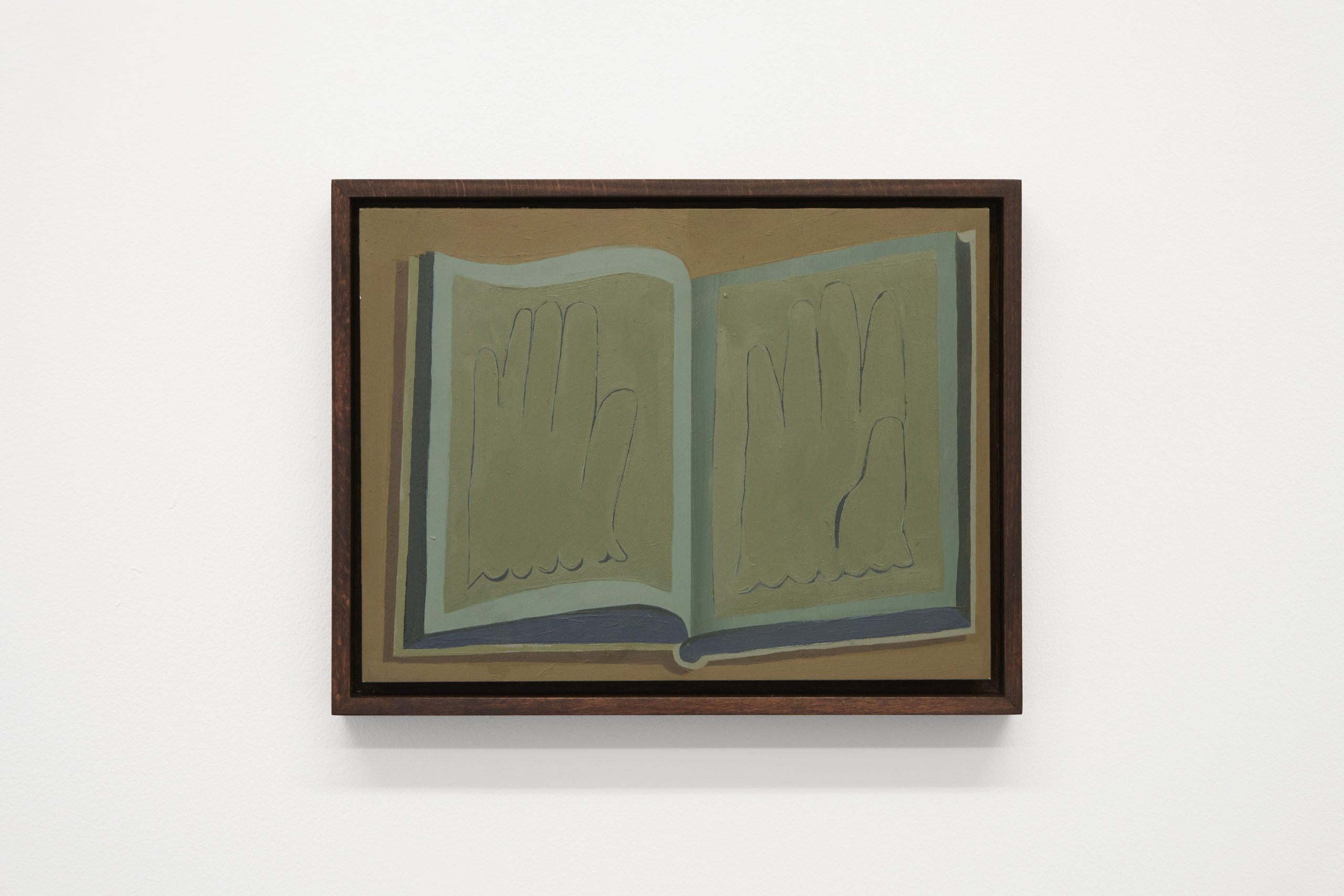

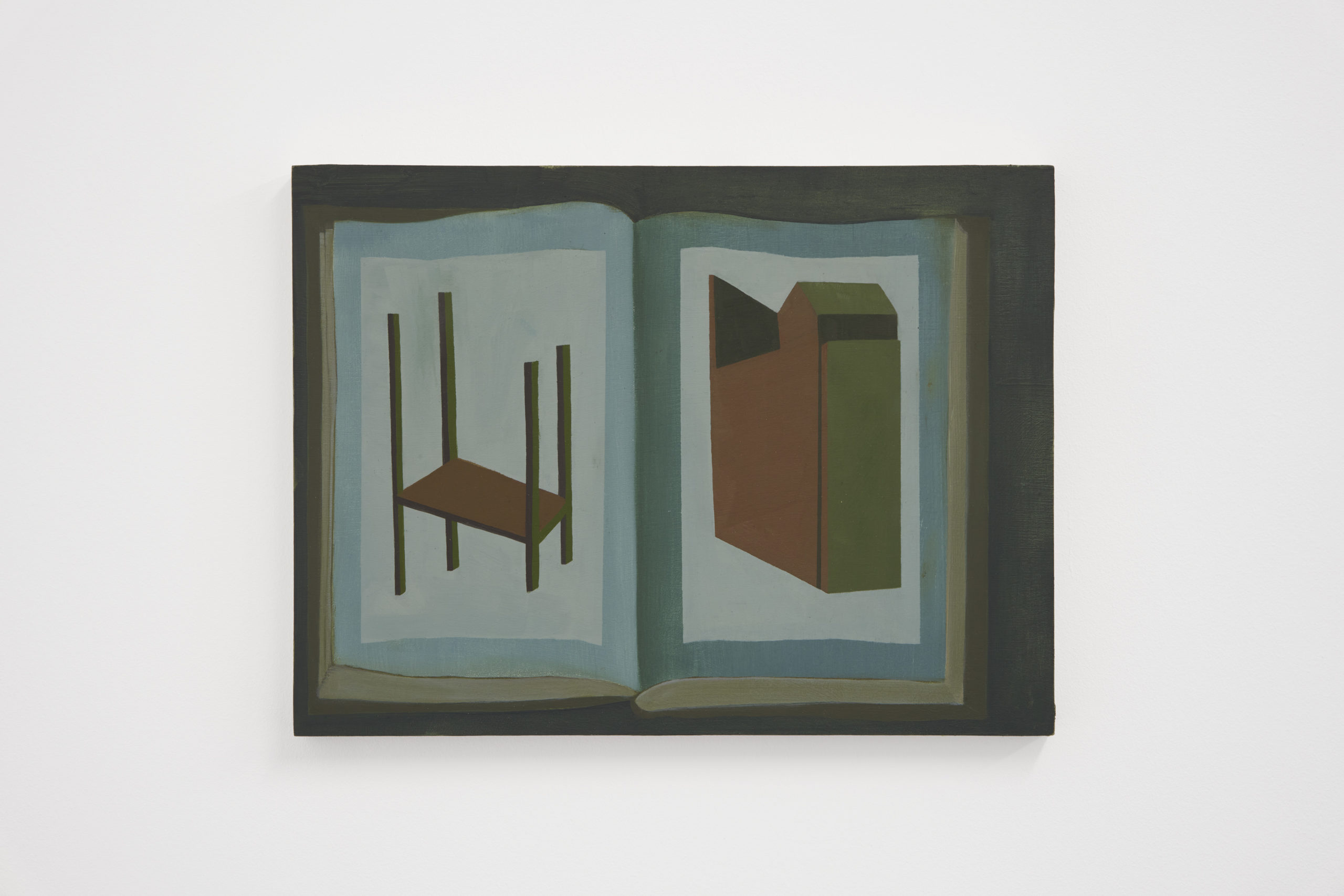

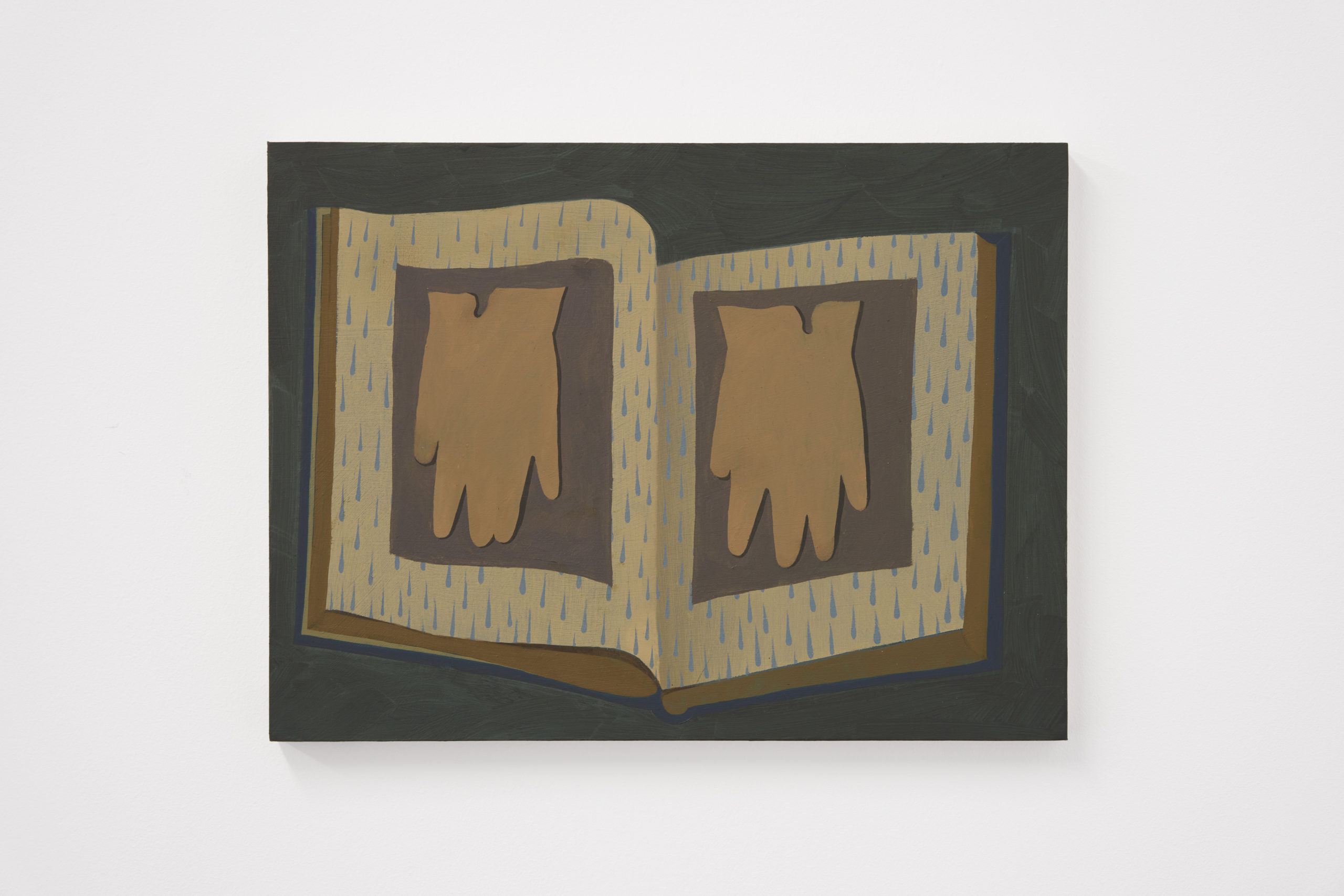

Silverberg’s paintings are marked by their quiet energy, muted palette and often small scale. Characterised by both a solitary stillness and an implied intimacy, she examines ideas of isolation, sickness and the relationship between interior and exterior worlds. Following a prolonged period of illness in her early adulthood, the artist’s subjects frequently include timeless signifiers of human care and comfort. Sick beds serve as analogous self-portraits; silhouetted structures act as architectural archetypes of the Mediterranean home; gloves personify a fashion-forward approach to protection or precaution; and, most recently, books embody an escape to that inviting inner realm. At once melancholic and reassuring, they suggest an inherent frailty and offer empowerment as coping mechanisms against our contemporary condition.

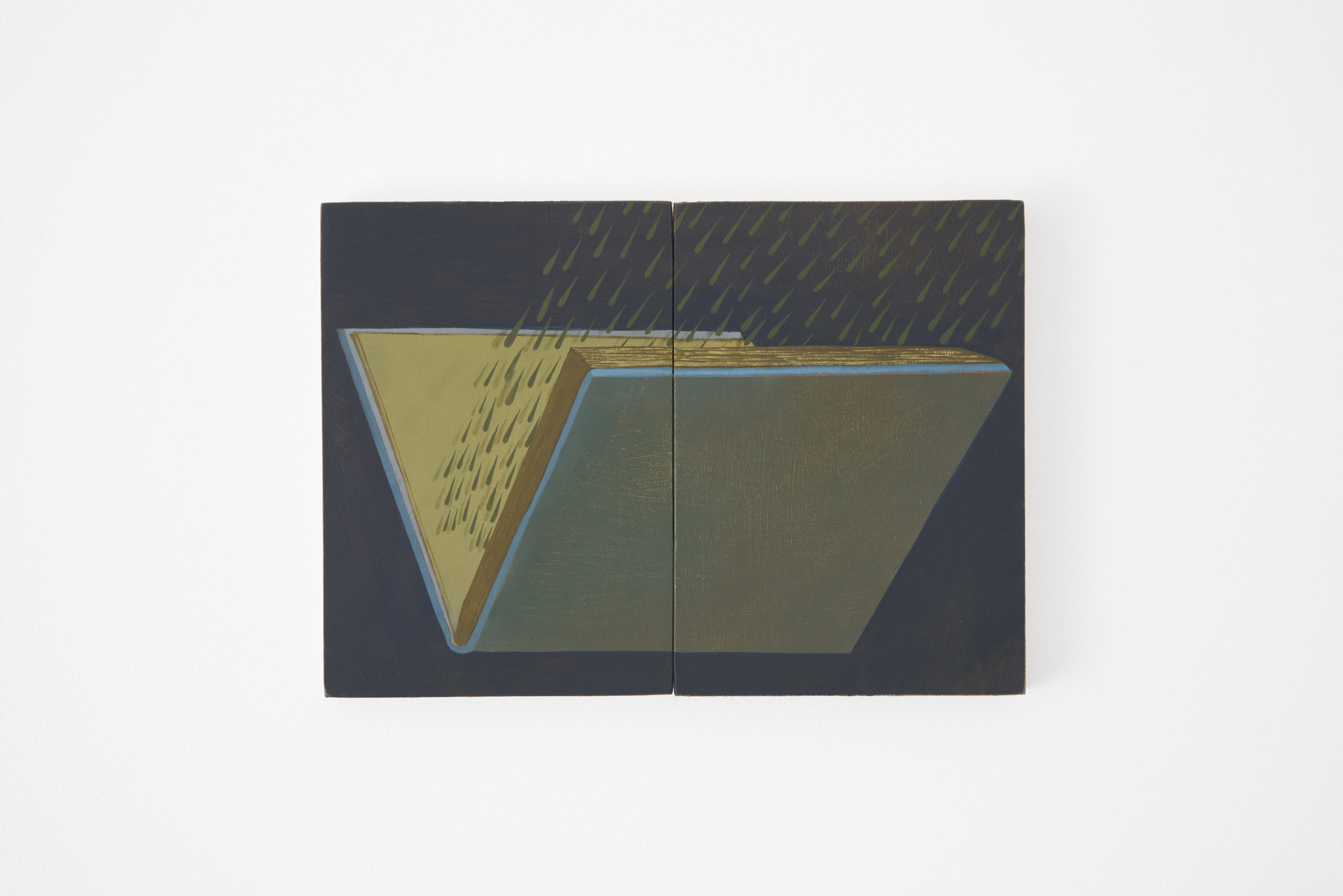

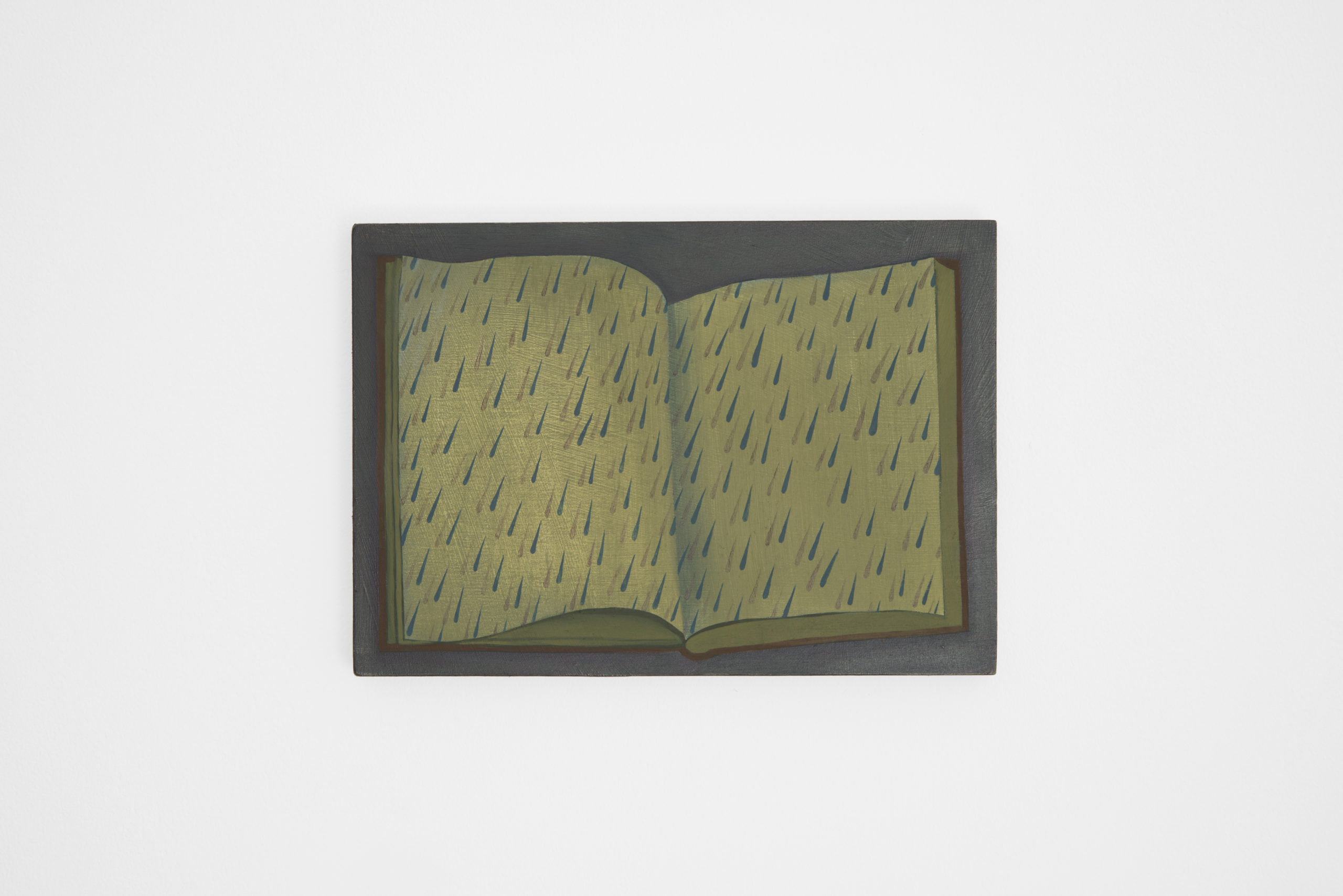

For her debut solo exhibition, Silverberg has turned to Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges’ short story The Library of Babel (1941) for conceptual consideration. The essay, laced with Latin-American magical realism, is a literary take on the infamous infinite monkey theorem, that states a monkey randomly tapping keys on a typewriter for an infinite amount of time will almost surely type any and all given texts, including the complete works of Shakespeare. Imagining the universe as a library of near-infinite interconnected hexagonal galleries, each filled floor to ceiling with books, Borges ponders the possibility and repercussions of the availability of all worldly knowledge. With no two books alike, and each containing a randomised combination of the available orthographic symbols – the letters of the alphabet, space, comma and full-stop – it stands to reason that within the writer’s seemingly limitless library would be housed the prophetic tale of every person’s life, including details of their future and ultimate fate. And so Borges, himself a librarian throughout his lifetime, envisions murderous hoarders of aspiring soothsayers marauding the narrow corridors and spiral staircases; men driven to insanity and suicide over the improbability of ever finding their fortune-telling tome; and illiterate adolescents sexually enamoured only by the alluring power of the printed occasional oracles.

Recognising paintings’ significance as a historical medium, the story suits Silverberg’s natural inclination towards an obsessive, meditative repetition. Her practice a process of self-referential self-discovery, motifs from previous paintings and bodies of work begin to adorn the pages of her open books. As surrogates of the subconscious, these painted journals become containers for not only the artist’s current concentrations but also a contemplation of previous artistic intentions and future proposals. In a poetic final act of prophetic fallacy, rain often obscures or surrounds the scenes, slanted and suspended in time as it stains the pages, a teardrop-shaped trope that the artist initially adopted following inspiration from Lorenzo Monaco’s predella panel Incidents in the Life of Saint Benedict (1407-9, housed in The National Gallery). Fearing her imminent demise and wishing to spend one final night with her brother Benedict, Saint Scholastica prays for a postponement of his departure. As a miraculous rainstorm rages throughout the night, it not only prevents Benedict’s exit but also provokes the siblings to engage in existential discussion and debate of life’s most meaningful questions. Questions to which one might seek answers in the great works of art or literature, and from which Silverberg seeks solace in her paintings.